It was the perfect battle of annihilation. In the summer of 1944 the Roman battle of Cannae in Italy was replayed on the Berezina in Russia

It was the perfect battle of annihilation. In the summer of 1944 the Roman battle of Cannae in Italy was replayed on the Berezina in Russia

In the opening days and weeks of the Allied invasion of Europe at Normandy in June 1944, the ether cracked and sparked across the English Channel with situation and intelligence reports coming into SHAEF (Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force) operational headquarters in Portsmouth at Southwick House, 75 miles south of London. These reports from the combat units in France contained the typical information a commander would expect: Battle progress, enemy force predictions, friendly and enemy casualties, unit readiness and morale, supply status, especially fuel and many other bits of military minutiae that painted the picture of life in the front lines.

However, among the thousands of reports, certain unusual items began to appear.

At first, just an odd mention or oblique reference. But as the invasion progressed into late summer of 1944, these references and mentions became more and more frequent.

These references had to do with the nationally, racial and ethnic make-up of enemy units encountered and captured with increasing frequency. Specifically, the reports described the German prisoners of war – or to be more accurate, the lack of ethnic Germans in the units encountered. A number of these prisoners captured in these opening weeks in Normandy were anything but the master race of Hitler’s Germany, his so-called supermen. What the Allies discovered was enemy infantry and panzer troops from all over Western and Central Europe, including Dutch, Danish, Norwegian and some French. But what specifically caught the Allied commands interest was that many of the soldiers fighting for the Germans, were far from their home countries, mostly from Eastern and Central Asia.

Among these captured soldiers from far away were former Russian Army Russians, Cossacks from the steppes of the Volga, men from Turkistan, the Caucasus and the far flung portions of the Soviet Union. There were even Indians[1], as well as Thais from Indochina. What were the Germans doing relying in men from such far away regions, most whom, by the way, had willingly surrendered to the Allies at their first opportunity? How had these men come to be in the German Army, some of them in the Waffen SS, the supposed cream of Germany’s land fighting units? The Germans were about to confront the most dangerous threat to its land forces in Western Europe, a force that had to be defeated and destroyed quickly and these men were to provide the edge in this decisive struggle? What was needed was the best men Germany could muster. However, not only were there no longer adequate numbers of Germany’s best and brightest; most of them not even in France for this momentous battle. Where were they? They were deep into the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics or Russia, confronting a far greater and closer threat to the German homeland.

[1] These troops arrived in the west in 1943 – 44 and were mainly from captured British Commonwealth units in North Africa. For more on the locations, activities and relationships with the local inhabitants of these units see Eastern Troops in Zeeland, The Netherlands, 1943 – 1945 by J. N. Houterman, Axis Europa, New York, 1997.

Byelorussia, Summer 1944: foreboding

When discussing the invasion of Normandy, one tends to think of it as the major turning point in the Second World War. Indeed it was. The successful landings in Normandy announced the arrival of the Allies’ return to the mainland of Western Europe, never to leave, their presence continually growing. What is less known in the West is that there was another turning point in Europe, in the same month and year, that was just as important and vital to the successful Allied accomplishment at Normandy. That was the Soviet June 1944 attack against the German forces in Eastern Europe and Western Russia in Operation Bagration.

Before Stalin launched Operation Bagration, the German forces in Russia enjoyed the ability to trade space and time, to outmaneuver and retreat in the face of superior forces and stave off disaster time after time despite Hitler’s frequent “stand fast” orders. It also spelled the end of the one-front war for Germany, the Wehrmacht in Italy notwithstanding. They also enjoyed the ability to transfer and deploy division-sized and larger combat units quickly and efficiently from one front to another via the Reichbahn, the German national railroad system. It was this rapid movement of enemy units that caused deep concern amongst Allied war planners and had to be prevented. The fateful month of June 1944 also brought the long awaited second front to the Allied war effort and Germany would now have to contend with the prospect of being caught in a vice-like position between East and West. Short of the Allied coalition falling apart, the sands of time were running out for Hitler. Russia was about to end the German dream of German Lebensraum or living space in the East.

The Opponents

With the end of the Spring rasputitsy[1] in early May the Russian buildup of men and equipment opposite Germany’s Army Group Center under the command of Generalfeldmarschall Ernst Busch did not go unnoticed. By June the front line configuration of Army Group Center came to be called the “Byelorussian Balcony”, an overhanging salient (Map 1, German-Russian Front Line 23 June 1944 ). Unlike the previous summers in Russia, the traditional German offensive campaigning season, this summer there would be no attack anywhere along the long front in Russia. The officers and men of Germany’s Army Group Center, made up of the following units: 3rd Panzer Army, 4th Army, 9th Army and 2nd Army, consisting of 52 divisions (34 infantry, two Luftwaffe field divisions, seven security divisions, two panzer grenadier divisions and one panzer division) spent the year constructing field fortifications along its 175 mile front in anticipation of a Russian attack. However impressive the units sounded, all were under strength in all areas of their organization: men, equipment, transport and air power, especially the 3rd Panzer Army which contained very few panzers, 553 panzers all toll, and most of these were assault guns or sturmgeschutz, turret-less tanks, good for defensive, positional action but with limited effectiveness in the often swirling world of tank vs tank combat.

The area of greatest concern was the state of the infantry divisions. The average division strength was not only depleted, but many of the divisions consisted of up to 33% Volksdeutsch, ethnic German’s from the borderlands of the Reich, Eastern Europe, Alsatians and Poles. They were not only unwilling to fight to the death of Hitler’s Germany, many were unmotivated and poorly trained and equipped. Although the 800,000 men of the Army group appeared adequate to deal with a Russian attack, almost half were support personnel, gathered up as the German armies retreated west in front of the Russian offensives of the last two years. The limitation of men and panzers was also reflected in artillery and aircraft; approximately 9,500 guns of all types and 839 aircraft, of which only 40 were operational fighters by the start of the attack. The most valuable aircraft for Germany at this period of the war in the east was ground attack aircraft, of which the Army Group only had 106.

The Red Army units preparing for the attack were everything the German units were not: almost full strength, well equipped, motivated and, with the assistance of the Allied Lend-Lease supplies now in 1944, becoming increasingly mechanized at the same time as the German forces were in decline in mobility because of interruptions in vehicle and fuel production due to the loss of manufacturing resources, combat and Allied day and night bombing of German industry.

A growing problem for Germany, in addition to its decline in fighting power, was Hitler’s meddling in military matters. Beginning in the winter of 1941, his insistence in holding ground in the face of the first major offensive of the Red Army, when most of the field commanders called for retreat, was the correct decision. However, this set a pattern of command behavior in which his intuition became more and more pronounced in his decision making, when the facts of the situation no longer matched reality. At a time when Stalin was allowing greater freedom amongst his field commanders, the opposite was happening in the Wehrmacht. It was to have fatal consequences for Army Group Center in 1944.

Marshal Zhukov gathered four Russian Front Armies for the attack, totaling some 118 rifle divisions, eight tank and mechanized corps, six cavalry divisions, 13 artillery divisions and 14 air defense divisions, some 2,000,000 men, an enormous and formidable force. The average strength of the Russian rifle division was around 6,000 men, still short of their authorized 10,000 man strength. Although smaller than a German division, at this period of the war, especially in the east, around 12,000 men, the difference was made up in attached support units, mainly mortar and field artillery units as well as tank and combat engineer battalions. Although the presence of six cavalry division might appear to be anachronistic, the Russians were aware of the terrain at and behind the German front line and these equestrian units were to prove their worth in the forests and swamps where tank and wheeled vehicles were at risk.

German Expectations

Hitler and the German military high command, the OKW (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht) and its component that managed the war in the east the OKH (Oberkommando der Heer) were fully aware that a big Soviet summer offensive was brewing. The big question for the generals in the east was almost the same as for those in northwestern Europe: where and when would the attack take place and what was the targets of these offensives? Examining the map of the fighting front in the east, the schwerpunkt, the point of maximum effort and, for the Red Army, the most logical direction of attack would be north-west, the shortest distance to the Baltic Sea in the Königsberg area would be an attack launched from the Kovel area of Poland, (Map 1, Option 1, German-Russian Front Line 23 June 1944). If successful, this single envelopment would trap two German army groups against the Gulf of Finland and the Baltic Sea. However there was one very big problem with this plan: it was the most obvious attack point of the front; the Russians knew it and the Germans knew it too. Also, Stalin had no need to trap German armies, his powerful armies were destroying them quickly enough. His goal was Berlin, due west. An attack of this kind was typically German in design and style, a surgical slice through the enemy front at its most vulnerable point continuing with a high speed drive for the target, the Baltic Sea. It was here the Germans expected it, it was where Hitler said it would come and they prepared accordingly.

German nachrichten or intelligence and gegenspionage counterespionage organizations, particularly Fremde Heere Ost (Foreign Armies East or FHO), under the command of Colonel Reinhard Gehlen, the organization especially tasked with eastern front intelligence matters, in addition to losing its edge at this stage of the war, had also been badly compromised by infiltrations of Russian intelligence and communist sympathizers in the military. This corruption of the intelligence organizations adversely influenced German command decisions and judgment. Postwar assessments of German agent success behind Russian lines indicate as many as 90% had been captured, killed or imprisoned. Part of the German intelligence problem was systemic and organizational. As German intelligence gathering was divided into two components, one operated by the Reichssicherheitshauptamt or Reich Security Main Office, abbreviated RSHA, and the Army’s Abwehr or military intelligence. The fact that these organizations were at loggerheads with each other severely limited their operational effectiveness. Adding to these difficulties was the general state of Russian domestic and civic paranoia instilled by the state security organs which made planting foreign or even ‘turned’ Russian POW agents vulnerable to detection. It was this lack of quality high level military intelligence that, in part, caused the surprise of the discovery of the T-34, KV-1 tanks and Katyusha rocket artillery in the opening months of the invasion in 1941.

In preparation, OKH stripped the best panzer divisions from the armies on the Eastern front and placed them in the 1st Panzer and 4th Panzer Armies in Army Group North Ukraine, located just south of the Kovel area, ready to launch a flank attack into the southern flank of the anticipated Russian attack. This left the remainder of the front in the east dangerously vulnerable to Soviet attack having little or no reserves. To shore up the front and make good the missing panzers, Hitler decreed the establishment of Feste Platz or strong points in front cities and towns in Byelorussia, most notably at Vitebsk, Orsha, Mogilev and Bobruisk. As will be shown, these strong points did nothing to slow the Red Army in its attack; it confined valuable troops and their equipment to certain capture and death and, most importantly, robbed local German command of the flexibility of mobile defense. It was a recipe for disaster.

Russian Plans

For Bagration, STAVKA, the high command of the Red Army, under the command of its Special Representatives, Field Marshal Georgi Zhukov and Alexsandr Vasilevskiy, was also aware of this ideal attack point and the attraction it would pose for the German planners. Field and strategic intelligence arriving at STAVKA indicated the Germans were anticipating just such a move by the Russians and their preparations preparing for it. However, almost four years of fighting the German Army in the East yielded lessons learned and one of them was not to attempt operations that not only were anticipated by the German enemy, but which the Red Army field generals were not capable of. The coordination, expertise and timing of the German way of mechanized war was still something the Red Army had not completely mastered. A Red Army under the thumb of Joseph Stalin still did not completely allow independent, on-the-spot, decision making in the field, vital for successful mechanized operations. Furthermore, a broader offensive posture would allow the Red Army to deploy its biggest advantage over the Germans, that of massed men, tanks and artillery. Also, with a broad front offensive, the potential of accidental or friendly fire was reduced, not this this was ever a priority in Russian planning.

The Russian choice was to crush the center of the German line in Army Group Center (Map 1, Option 2, German-Russian Front Line 23 June 1944 ). The reasons and practical utility appealed to the Russian operational planning element of simplicity. It was also the shortest distance to Berlin via the line Minsk-Warsaw-Berlin. It would eliminate the threat of Luftwaffe air attack against Moscow by putting German bombers out of range and remove the overhanging threat of a flank attack against Red Army units in the 1st Byelorussian and 1st Ukrainian Fronts.

The final attack plan for the Soviet 1944 summer offensive, to use its official title; The Byelorussian Strategic Offensive Operation, would cover a front area from Polotsk in the north to a point south of Pinsk in the Pripet Marshes. Arrayed in this area from north to south was the 1st Baltic Front under General of the Army I. Bagramyan, 3rd Byelorussian Front under Colonel General I. D. Chernyakovskiy, 2nd Byelorussian Front und Colonel General G. F. Zakharov, and the 1st Byelorussian Front under General K. K. Rokossovsky.

The offensive would consist of a series of small offensives, from north to south, initially softening the German positions, then breaking them open to permit the mobile units to begin larger envelopments and exploitation. The first of these would begin in Finland around 1 June to finally remove this co-belligerent from the German order of battle and to provide a distraction from the main event farther south. The focus of the Russian effort would then begin with the intent to not permit the German defenders to retreat to prepared positions further behind the front line. The now more mobile Red Army, thanks to western Allied Lend-Lease trucks[2] and Jeeps as well as new rail rolling stock, now enabled the Red Army to pursue the retreating Germans faster than ever before, permitting deep penetrations into rear area positions and disrupting the expected German counter attacks.

The Russian preparations for the offensive were thorough and extensive. Having learned from painful experience to minimize and conceal preparations from German air and field reconnaissance, especially their ability to “listen in” to radio traffic, the Red Army went to great lengths to camouflage the transfer of combat units to the attack site. This covering or masking of preparations is called maskirovka in Russian. The amounts of material accumulated for the offensive were just as impressive as the numbers of men: Artillery, 28,613 (all types), aircraft, 6,334 (all types) and tanks 4,070 (all types).

With the Leningrad and Karelian Fronts in the north attacking the Finns, the beginning of Operation Bagration began more subtly in Byelorussia, in some places many miles behind the front line. Around the end of the first week of June, STAVKA instructed the partisan detachments behind the German lines in Byelorussia to begin what was called the “rail war” against German communications. Although diverting and unsettling, the total effect of these attacks were muted because of ongoing German anti-partisan operations in the Byelorussian region. The seven German security divisions were fully engaged in preventing any disruption in their rear area facilities and communications. The best the partisans could do was to stop German rail movement for about a day or two. Regardless, the lack of “peace in the rear” and partial disruption in rail movement at this critical time contributed to the disaster that was coming.

The Attack

Despite the extensive efforts to keep the reinforcements from being detected, the weary veterans of four years of fighting the Russians had, like most experienced field soldiers, learned to “read” the enemy lines. Despite the Russian efforts to deceive or conceal them, German radio intelligence listening stations reported new radio nets originating from Russian units not detected previously, indicating the presence of new units in the area. In the trenches there was a real sense that something big was going to happen, it was the “gut feeling” of many of the German sentries and infantry in the line. By mid-June the summer weather had turned hot and dry and the ground, despite the generally marshy terrain became hard and dusty. The morning routine was unchanged, as it had been for months, there is the usual 4 or 5 plumes of wood smoke from the Russian side, probably from the field kitchens. But recently, as May turned to June, more are noticed, soon it is a dozen, several days later it is too many to count as they begin to mix and blend together. Even the birds, so plentiful in this damp region, had disappeared.

At night there is the usual sounds of life at the front; the regular firing of flares to light the no-man’s land between the opposing positions, the occasional rip of machine gun fire, or the crack of a bursting hand grenade checking some perceived patrolling maneuver in the dark. Occasionally one might hear the sound of an engine, but it’s usually the battalion chow wagon or a staff car from HQ. But in the last week or so, the usual motor sounds have become deeper, different and muffled, the sound of engines, many engines. These engine sounds are not from Russian made trucks and cars, these sounds are new. The new engine sounds come from American trucks and Jeeps and generate worried comments in the dark among the sentries, the sound they make is different from the Russian engines. But what worries the tired Germans most is the big engines, the deeper sounds they hear. What they are hearing is the newer up-gunned T-34, the T-34/85 tanks, and the new ‘big brother’ the JS-2 heavy tanks, mounting a 122mm main gun. As the days grow closer to the attack date, the sounds of the engines become more numerous, louder and closer, some men back from patrols report that they heard the actual clanking of tank tracks. There were many of them, far too many, many more then the Germans had.

The artillery began the opening moments of Operation Bagration on 23 June 1944. From north to south the firing grew in intensity and the millions of men, thousands of tanks and aircraft added to the ear bursting roar. The death of Germany’s Army Group Center was beginning. The first week of the Russian attack was relentless and aggressive. The Germans were stunned by its location, direction, ferocity and scale. The operation was to last 68 days and the attack frontage spanned a length of some 620 miles. The Germans had badly miscalculated the focus of the Russian summer offensive, and with the panzer divisions away in Army Group North Ukraine and Army Group South Ukraine, Hitler’s restrictions on unit maneuver, the rigidity brought on by the Festung cities, the brittle German front collapsed quickly and completely.

By the end of June Bobruisk was encircled and Borisov was retaken. In early July the Berezina River was crossed along almost its entire length. The content of radio messages flowing into Army Group Headquarters demonstrates the enfolding scale of the disaster. Phrases such as “completely encircled”, “4th Luftwaffe FD (Field Division) no longer exists”, “the commander of 134th Division has shot himself” and “division command no longer has control over the division” and “confusion reigns” describe the magnitude of the unfolding disaster along the German front. Reports of failed breakout attempts, of lost, wounded and missing commanders and men filled the airwaves. This was no diversion for an operation at another part of the front, this was the feared Russian main attack and the German forces were not ready for it. It was the summer of 1941, with the roles reversed.

This was an astounding development for an army that prided itself on its discipline, Prussian discipline! Their historic ability to withstand any enemy, any weather, any discomfort, and persevere was the hallmark of German military training. The wholesale destruction of an entire army group from a nation the size of Germany staggers the imagination, it certainly did the German one. Whole divisions disappearing, generals shooting themselves, divisions out of control? These things happened to other, more primitive armies; the Russian Army perhaps, certainly not the German Army. Losses on this scale were unsurpassed; even the terrible winter before Moscow in December of 1941 (110,000 casualties) and the white hell of Stalingrad of 1942-1943 (231,000 casualties) pale in comparison.

With the situation now completely out of hand, Hitler, infuriated with the unauthorized retreats of the Army Group, on 27 June replaced Field Marshal Busch with one of his favorite generals Field Marshal Walter Model, who had earned the nick-name of “Hitler’s Fireman” for his frequent assignments to threatened sectors of the front.

Conclusion

By the end of August the Russian juggernaut was beginning to ebb. Exhaustion, dwindling supplies and German reinforcements pouring in from all over Eastern and Central Europe finally brought Operation Bagration to an end. In the north Riga in Latvia was threatened, Vilnius and Brest-Litovsk were taken and the troops of Rokossovsky’s 1st Byelorussian Front were across the Vistula River from Warsaw. In almost two months the Russian armies had advanced, in some places, 450 miles and had destroyed Germany’s Army Group Center, (Map 2 German-Russian Front Line 23 August 1944). 200,000 were killed, wounded and missing, including 10 generals, some 150,000 captured, including 23 generals. Germany lost some 30 combat divisions in the battle and were never able to replace them with experienced combat personnel.

The battle was also costly for the Red Army: 771,000 were killed, wounded or missing, an average of 11,337 men per day. However, the Red Army could take solace in that the final portions of Mother Russia were retaken and the war had now advanced into Poland and the first Russian boots were about to rest on German soil in East Prussia.

Operation Bagration was also significant in one other action of the war. The devastating losses in Byelorussia set in motion, for the last time, an attempt on Hitler’s life. The losses breathed new life into the German Army’s underground resistance movement when Oberst (Colonel) Count Claus von Stuaffenberg placed a briefcase bomb in Hitler’s temporary conference room at Rastenburg, East Prussia and because of fate and happenstance, missed the final chance to remove Hitler from command.

The Inter-Front Connection

After the huge losses of men and material by Army Group Center and the need to rebuild the Army Group and halt the Russian Army as quickly as possible, the immediate task for Germany was to stabilize the eastern front. The loss of 30 divisions was going to consume the final reserves of men and material the Wehrmacht possessed. With this emergency operation at hand, the transfer of any combat units from the Ostfront to anywhere the Allies threatened, to the South or to the West was almost certainly out of the question.

The Red Army had not only destroyed the most potent of Germany’s field armies and opened the door to Berlin and Central Europe, the threat of an inter-front transfer of units to defeat the Western Allies at Normandy was also eliminated.

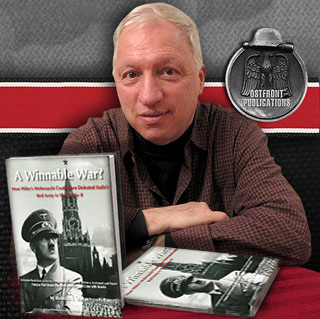

Editors Note: This article is an extract from Why Normandy Was Won: Operation Bagration and the War In the East 1941 – 1945 by Kenneth C. Weiler, Ostfront Publications, LLC, ostfrontpublications.com ISBN: 978-0-9825779-0-5, kweiler1@comcast.net.

This is the spring and fall rainy season in Russia. With most roads in Russia unpaved in the early 1940’s, this seriously impeded the rapid flow of German units in the U.S.S.R., something the Wehrmacht had become dependent upon in their tactical and strategic operational planning.

A large number of the trucks shipped to Russia as part of the Lend-Lease program were manufactured by Studebaker. So dependable, durable and rugged were these vehicles, the name Studebaker was synonymous with truck in Russia for decades after the war.